Is the grid too good? An examination of grid-based road systems

The benefits to mobility provided by grid-based road layouts are manifold, but is better mobility really what people want?

Grid-based road systems are ubiquitous in urban areas around the world, but many suburban areas avoid them. We sat down with a land-use planner to learn about the advantages of grids, and why people might choose to avoid them.

Efficiency and Mobility

“People like options, and the grid systems provide options,” says Vivian Roe, who has worked as a land-use planner for Sarasota County, Florida for sixteen years. “The best thing about a grid designed road system is there are multiple ways to get around to go from one place to another.”

Modern cities are multi-modal; delivery trucks share space with public transit and bikes share space with e-scooters. Add to that the rise of the hailing and delivery economy. “The new part of the industry is the drop off and pick up,” Roe says. “Before where people used to go to the grocery store or the drugstore, they don’t do that as much… also the Ubers of the world, [and] Uber Eats. That’s a whole new industry that the road systems, quite frankly, are not designed for. So the grid system always helps with that. If there’s a traffic backup in a certain area, a driver can find many alternate routes around the problem area.” Streets with cul-de-sacs do not provide the same options.

The same principle applies if there’s an accident, construction or a school zone. The grid gives travel options.

You can take advantage of those options without fear of getting lost thanks to the grid’s other mobility benefit: navigation. “Because you can orient something as North-East-South-West, giving directions is super easy,” Roe explains. In the era of HERE WeGo, this might not seem like much of a perk, but it still has its usefulness in case we are unable to rely on navigation applications.

One last thing to consider is how the grid develops organically. Roe explains, “As far as the type of planning that we do, we build roads to connect. Designers connect existing points of activity to future points of activity. Engineers know straight lines; they’re the most efficient. Which leads to a grid system.” Of course, topography such as rivers and hills have to be taken into account in the roadway designs.

Suburban Rebellion

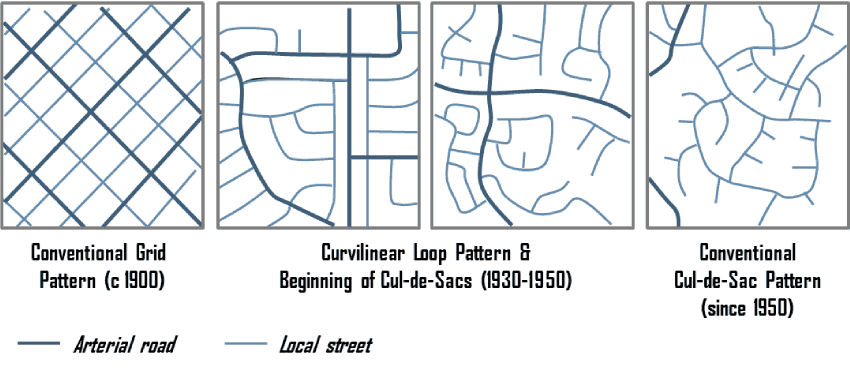

Suburbs, mixed-use but predominantly residential communities intended for commuters of a denser urban area, were once a peculiar American phenomenon, but are gaining popularity in Europe. “The early suburbs used to be on a grid system,” explains Roe, “but in the 70s and 80s developers got away [from grids]. That’s when cul-de-sacs and the gated community were birthed.”

Given all the stated advantages of grid-based road systems, why the change? “People like options, but at the same time, where you live, you don’t necessarily want much traffic going by your home. You want your kids to be safe, maybe playing in the street. Curvilinear streets also help to limit speed. It’s not just an objective of getting from here to there; it’s also about safety, and to help mitigate traffic noise in the neighborhoods.”

A tale of two HERE cities

HERE Technologies has headquarters in Chicago, USA and Berlin, Germany. Chicago is famous for its grid system of roads; look at it on a map and you’ll see a neat array of orderly right angles, with only a few diagonal lines for express travel. Look at a map of Berlin and you will see roadways that are connected, but anything other than neat and orderly. Is a clean grid the way to go? Should our Chicago office convince our Berlin office to petition the government for a straight road from Buch to Britz?

Consider what Vivian Roe mentioned earlier about navigation, with this example:

In Berlin, to get from Lichtenberg to Heinersdorf, just go West-Southwest on Landsberger Allee, turn right going Northwest on Weissenser Weg, turn right again on the Berliner Allee motorway heading North/Northeast, exit heading Northwest on Rennbahnstrasse, and keep following the road as it zig-zags and turns into Romain-Rolland-Strasse. Three and a half miles as the crow flies, five roads, three turns, several directions.

In Chicago, to go from Back of the Yards to West Loop, go East on 47th Street, turn left and go north on Ashland for twenty-four blocks. Three and a half miles as the crow flies, two roads, one turn, two directions.

It seems like Chicago has a clear advantage in terms of mobility, but that’s not the whole story. Using the HERE Urban Mobility Index, we see that although Chicago is grid-based, it has significantly more traffic congestion than Berlin.

While this deserves its own dedicated study, Roe sheds light on one possible factor:

“What’s important is not that the pattern is a grid, but that the streets are connected.

The pattern of the 2nd to left below can work almost as well as the grid because there are (almost) no dead-ends or cul-de-sacs.”

So despite being bereft of right angles, Berlin streets still offer the options necessary to aid mobility and ease congestion.

The Challenge

Planners and developers are working to balance the desires of users for privacy and safety with the mobility needs of the future. As cities continue to expand, how will they deal with the non-connected streets of suburbs?

We offer our gratitude to our expert, Vivian Roe, for sharing her time and expertise on this article.

Have your say

Sign up for our newsletter

Why sign up:

- Latest offers and discounts

- Tailored content delivered weekly

- Exclusive events

- One click to unsubscribe